Although the coronavirus pandemic has caused some considerable problems with research and the sudden reorganisation of teaching, it has also opened up some opportunities that I wouldn’t ordinarily have had to network, attend conferences and hear about other people’s research. As an early modernist working in a department where there aren’t all that many of us, this has been really very useful – if I’m honest, I haven’t taken as much advantage of this as I should, but it’s hard work working and homeschooling through lockdown. So a few weeks ago, fresh from PE with Joe on YouTube, I went to MEMSFest, hosted by the University of Kent’s Centre for Medieval and Early Modern Studies. This is the first of a pair of posts about the conference.

In the opening remarks the organisers drew attention to MEMS Library Lockdown – a list of resources that we still have access to even though we’re in lockdown – and we were invited to their online seminar series. The first panel I attended was on Emotion and Embodiment and was chaired by Róisín Astell. First, Francesca Saward-Read talked about the early stages of her research into Audience Culpability in Early Modern Drama, exploring the differences between modern audiences – how do you gauge audience reactions when they’ve been dead 400 years – perhaps by accepting that it wasn’t If they felt something but What they felt. Examples were taken from The Spanish Tragedy (Kyd, 1585), Hamlet (Shakespeare, 1601), and The Revenger’s Tragedy (Middleton, 1606). Soliloquies and asides are direct connections to the audience. Hamlet is well known for soliloquies, of course, charting his descent into madness but dramatic features such as this allow the audience to connect with the performer. She explored how asides and soliloquy heighten the emotion of the scene, and make the audience part of the play, speculating on whether this made them partly culpable in the crimes of revenge tragedies. She suggested that we also need think about physical performance space and how it affects the original audience. She pointed out that the physical space created cohesion between audience and action – lighting, for example, was the same for both so they could be seen. There was very little separation to limit the setting to the stage.

Anna-Nadine Pike then presented a paper called “Spekyngly silent”: Moments of Irrationality in The Cloud of Unknowing. She talked about how the Cloud author dealt with the fact that apophatic theology believed that God was unknowable and could not be described by language. It was a way of attempting to quiet the mind and attain a state of contemplation. The Cloud of Unknowing recommends its readers should approach the text with love rather than intellect, allowing them a ‘nakid entente directe unto God’. Once this is attained the rest of the text aims to prevent the reader thinking logically and interrogating the text with its rational mind. It makes it clear that they should be grappling with something unimaginable. The text invites the reader to choose a word to contemplate – the language is use performatively by its readers.

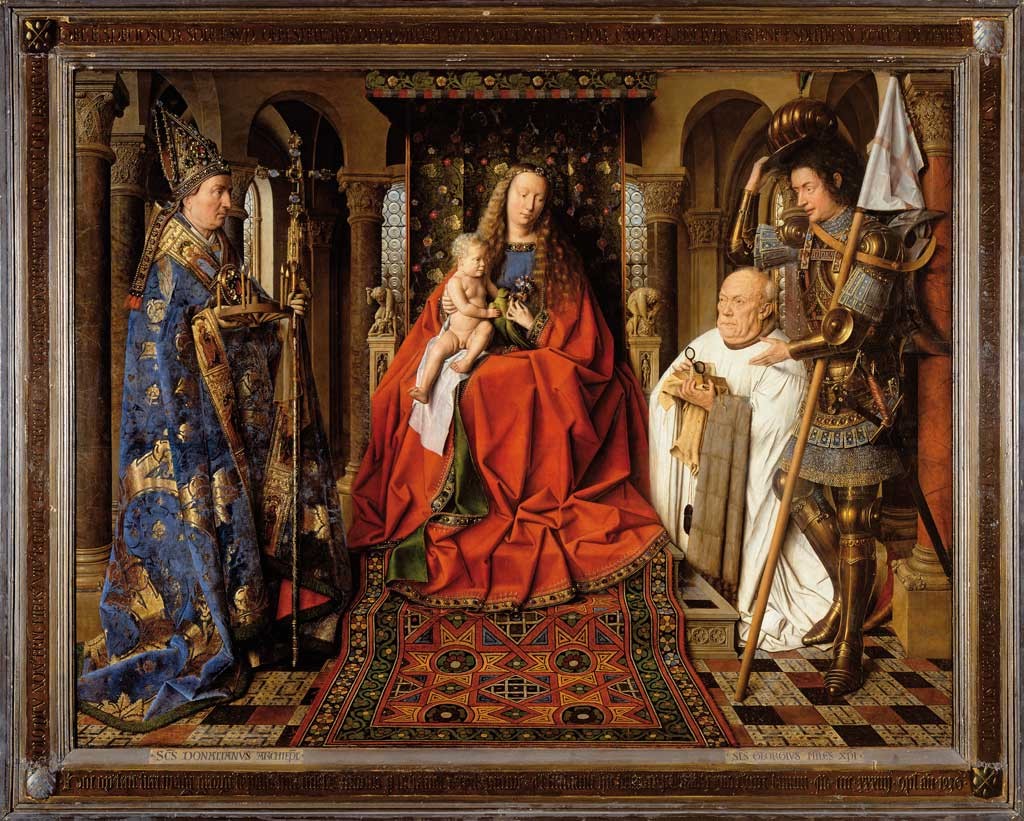

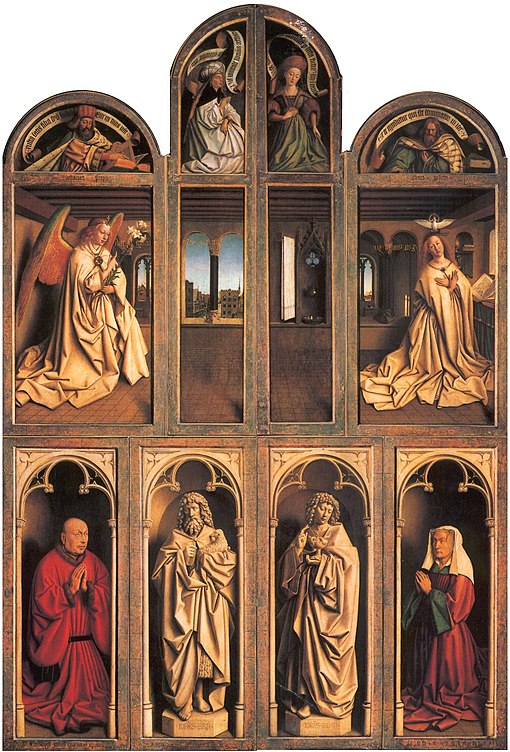

The next paper was from Lydia McCutcheon on Familial Relationships in the Miracle Collections for St Thomas Becket and the ‘Miracle Windows’ of Canterbury Cathedral. On the 800th anniversary of Becket’s death, she argued that familial relations in the miracle stories are central to the way that the monks helped to shape the monk’s veneration. The Miracle Windows have different shapes and numbers of panels, and each sequence is recorded in one of the miracle story collections. Lydia’s research has sought to identify familial relations in the Miracle Windows, then looked at the nature of the relationship. They are mostly loving, but they are not all simple, stock characters. This raises questions about their function and the way that the artists used the families to create Becket’s cult. Even in the stained glass, she argued, we are more invested in the characters because of their familial relationships. The final paper in the panel was given by Jordan Cook, who talked about Embodying the “Earthly” in Early Netherlandish Painting. Art historians face a challenge in deciding whether a setting is meant to embody an earthly or a celestial space. Her first example was The Virgin and Child by Jan van Eyck. It’s a very natural painting, but many scholars have used clues such as fantastical architecture show that it’s not a real, earthly space. Jordan looked at the imperfections in the Netherlandish spaces suggest a more earthly reading. She pointed out that, from a divine point of view, time happened simultaneously. This means heavenly spaces cannot be changed by the passage of time, while earthly spaces withered and decayed over time. Why would a heavenly setting include things like cobwebs or chips in stone, such as those that are seen in the Ghent Altarpiece by Hubert and Jan van Eyck? The inclusion of these worldly imperfections are useful details for artists concerned with naturalism. These principles are still used today by digital artists and architects.

Leave a comment