This year, the Historical Association conference moved online, with mainly pre-recorded lectures available for several weeks before the conference and live Q&A sessions during the conference week itself. This meant that I could not only flit about between lectures much more, but also access them in an order that suited me. This is the second in a short series of posts about the conference.

One of the things I love about the HA is that it brings together people from all walks of life who are interested in history – it’s not just for academics, or the public, but for history teachers too. This means that at the conference, I can keep an eye on useful teaching strategies, which is something that I think often gets overlooked in higher education. It was with this in mind that I listened to Using academic literature to enhance students’ subject knowledge and history-specific vocabulary at A-level by David Brown and Amy Diprose, of The Sixth Form College Farnborough.

They started by outlining why they thought that explicitly teaching subject-specific vocabulary matters, basing this on research into the literacy levels of GCSE students. The ability to comprehend meaning begins with word recognition, and research has shown that the gap between levels of word recognition in families of different socio-economic backgrounds is already significant by the age of 3. Then when students move from primary to secondary school, pupils are exposed in a single day to 3 or 4 times as much language as they had been at primary school. This means they cannot use their normal strategies such as looking at context, to work out what words mean.[1] But of course this isn’t all they are doing, so their brains are trying to do this at the same time as learning subject content and activating knowledge schemas. It’s a lot to do. Amy pointed out that a similar thing might happen at the transition to A level, and this made me think (again, as it’s something I’ve been thinking about a lot) about how we might approach the transition to university, as the same thing is happening. Anyway, the Oxford Language Report Bridging the Word Gap at Transition recommends explicit teaching of vocabulary, which is planned into the curriculum so that it builds up cumulatively throughout the years. It also recommends teacher modelling and promotion of rich, complex and specialist vocabulary so that students see and hear it used, as well as visual representation of words.

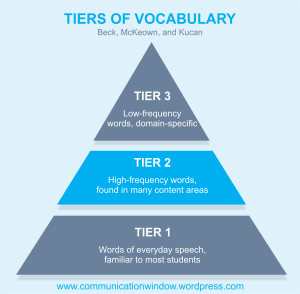

The question is, which vocabulary do you need to teach, and which can you ignore? The key is to identify which ‘tier’your vocabulary belongs to: [2]

Explicit teaching of tier 3 is normal, but we tend to assume that they will just ‘get’ tier 2. In fact, these are the most beneficial to teach because they can often be used in many contexts.

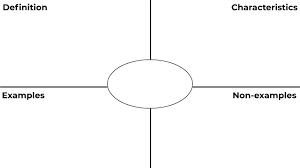

One way of approaching this is to get students thinking about morphology – the way parts of words are in fact building blocks which can be combined in different ways – and etymology – the study of the origins of words. This draws on existing knowledge and connects new words to old. Amy recommended the Frayer Model for teaching vocabulary, as it uses examples. [3]

David then explained how his school had applied these techniques through the use of essential readings with his 6th formers. Selected articles and book chapters are set throughout the course, with whole lessons based around the readings, not just questions on the readings for the students to answer and then move on. This sounded quite familiar – it’s basically what we do in university seminars! I was also mildly amused by the fact that this college is setting long book chapters right from the word go, with questions, in a way that some of my university students over the years have complained about!

Suggested key questions for essential readings focussed around three main areas:

- Are there any areas you didn’t understand? Are you still unsure about anything?

- What is the overall impression you get from the reading?

- What are the key arguments? (these can be specific questions about the arguments the author makes in order to ensure that students have understood and can summarise them)

But one of the key problems with history readings is that GCSE students are used to reading large literature texts, but they only read a few paragraphs of history texts at a go, so they aren’t familiar with the vocabulary. David then decided to make students print out the history texts and annotate them, following the same process with every text:

Complete the next essential reading. You will need to print this out and annotate it (this should include adding a summary of the key points in the margin every two to three paragraphs, highlighting key words, taking notes). This will be our process for each essential reading you complete going forward. You also need to update your vocab sheet with another 5 words from the essential reading.[4]

| Word | Meaning | Use in Sentence | Related words (synonyms) | Etymology |

Then the teaching of the lesson involves having the reading on the desk in front of them. The long discussions are always used to relate the readings to useful activities, such as how it would be useful for essays. But in terms of the vocabulary, they are brought carefully into the discussion on a regular basis, reminding students to check their notes when they have met a word before. Then the students are tested regularly on their word lists by using them in questions (eg Why might a political vacuum have an adverse effect on a poorer country?). Amy reminded us that language only becomes embedded when it has been used 7 times, so this process can be time consuming, but without the students accumulating these language skills they are unable to comprehend the texts fully. So overall, by explicitly teaching vocabulary, you save time in other areas because the students are better able to recall and use their subject specific vocabulary in other classroom and homework activities – and of course the exam!

[1] Alison Deigan, Bridging the Word Gap at Transition.

[2] https://communicationwindow.wordpress.com/2013/11/17/what-is-tier-two-and-academic-vocabulary/

[3] https://www.n2y.com/blog/language-and-literacy-frayer-model/

[4] David Brown.

Leave a comment