This year, the Historical Association conference moved online, with mainly pre-recorded lectures available for several weeks before the conference and live Q&A sessions during the conference week itself. This meant that I could not only flit about between lectures much more, but also access them in an order that suited me. This is the third in a short series of posts about the conference.

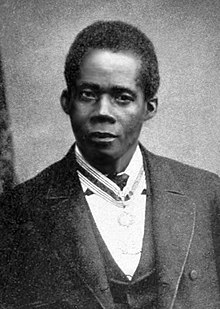

Having listened to all the lectures for the sessions I would be chairing at the conference, I was then able to move on to some of the other content, such as A history of Pan-Africanism by Hakim Adi, of the University of Chichester. Adi’s lecture was a fascinating overview of the development of the Pan-African movement over the long term. He argued that we might see its roots in the 18th century Sons of Africa, which included men such as Olaudah Equiano, who were concerned with activities such as human trafficking. They clearly thought of themselves as African despite living in London and concentrated on their common problems despite coming from different places. He pointed out that sometimes groups of Africans managed to find common language and cause in order to liberate their new countries, and he argued that we could see the Haitian revolution as Pan-African – it became a symbol of African achievement until the mid-20th century. He also talked about key 19th century figures such as Edward Blyden, who produced one of the first Pan-African newspapers and was seen by contemporaries as one of the leading fighters for Africans.

But the modern Pan-African movement really began in Britain when the London Pan-African Conference was held in London in July 1900. This was the first time the phrase ‘Pan-African’ had really been used. Although it’s often associated with Henry Sylvester Williams, the actual inspirer of the conference was an African woman called Alice Kinloch who came to Britain on a lecture tour talking about the problems that Africans faced. The conference was hugely important in highlighting problems around colonialism and racism. Du Boise presented a report at the conference which included the famous line that the problem of the 20th century was the problem of the colour line. Du Boise organised a series of Pan-African Congresses. The first was held in Paris in 1919. Student activism was led by Bandele Omoniyi, a Nigerian student at Edinburgh who wrote ‘A Defence of the Ethiopian Movement’, the Ethiopian Movement being another term for Pan-Africanism. Other activities in the early 20th century included a black beauty competition. Marcus Garvey was one of the main activists of 1920s. He set up the Universal Negro Improvement Organisation, which was established in Jamaica and then re-established in New York. It soon had more than a million members. He is best known for the slogan, ‘Africa for the Africans at home and abroad’, symbolic of his campaign for the return of African territories, such as the former German colonies, to Africans. He also set up the Black Star Shipping Line to trade between west Africa and the Caribbean in order to encourage black self-reliance. Of course, Adi also talked about the Black Power movement and the Black Panthers, and even brought the lecture up to the end of the 20th century with the African Union and into the 21st with Black Lives Matter.

I was also able to listen to Steven Gunn’s fascinating account of Accidental Death in Tudor England, from which the take-home messages included don’t fall asleep at the reins of a cart and don’t dance round the kitchen! To some extent, the information here was much as you would expect, given that accidents with livestock were more common in livestock raising areas and death by rockfall was more common in the Lake Disctrict. Nevetheless, Gunn was able to bring out some interesting aspects such as the way that the progress of enclosure can be tracked through particular types of accidental death. I was also interested to hear about how to cross a river – sometimes ‘bridges’ might only be 6 inches wide, so it’s hardly surprising that plenty of people fell off them and drowned, or that people chose to pole vault across rivers instead.

Such is the wide-ranging nature of the HA Conference that I was able to follow this with a fascinating update on American Civil War historiography (The Civil War Among Civil War Historians – Adam Smith, University of Oxford), and an insight into the visits of indigenous Americans to England (Legacies of Empire: Native North American Travellers to Britain, David Stirrup and Jacqueline Fear-Segal, University of Kent), although in the case of these two lectures I wasn’t able to take any notes because I had to listen while I was doing other things… One of the simultaneous blessings and curses of online conferences!

Leave a comment