A keynote paper given at The Experience of Loneliness in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries Conference, 29-30 June 2021

Postscript: In August 2022, after 8 months of negotiations, I was given a 2 day a week indefinite teaching and scholarship contract and a 2 day a week indefinite teaching and scholarship contract with an end date two years later at my institution. I would like to thank my colleagues, especially the then head of department, Ian Gregory, and my UCU branch for helping me to achieve this. Sadly, the indefinite contract with an end date was not renewed in 2024, despite the best efforts of my colleagues from across the department and the wider university.

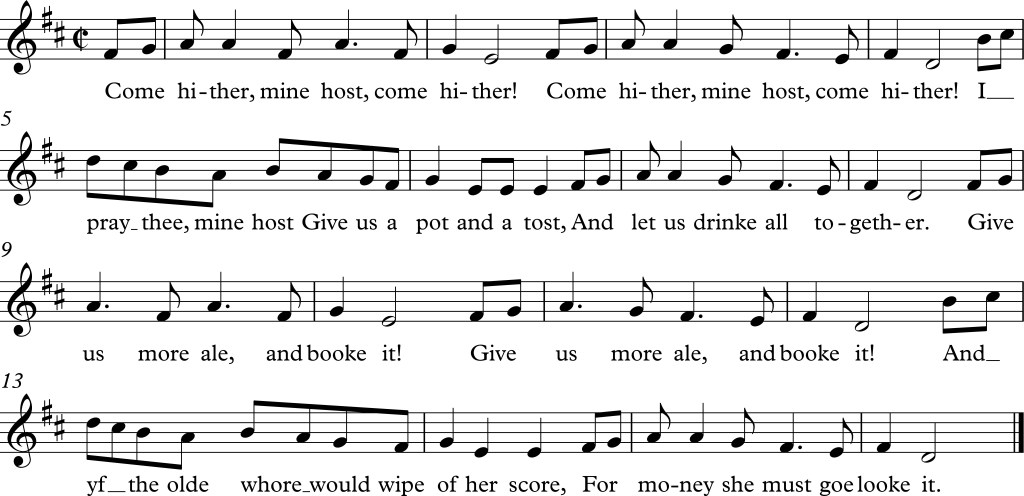

Come hither, mine host, come hither!

Come hither, mine host, come hither!

I pray the, mine host,

Give us a pot and a tost,

And let us drinke all together.

Give us more ale, and booke it!

Give us more ale, and booke it!

And yf the olde whore

Would wipe of her score,

For money she must goe looke it.[1]

Loneliness isn’t a thing in my field of work. My main area of research is the sixteenth-century ballad. These were the pop songs of their day. They were printed on large sheets of cheap paper and, as such, they are often known as broadside ballads, although the genre was not made up exclusively of printed material – they often circulated in manuscript or simply in the oral tradition. Printed ballads often included decorative borders; woodcut images which were reused from one sheet to another; and long, loquacious titles. They were sold by travelling hawkers, pedlars and balladeers who moved from place to place, selling their wares to whoever was willing to listen and to buy. These men frequently combined more than one occupation to make a living. The itinerant ballad seller Richard Sheale, for example, was also a retainer of the earl of Derby, while the master balladeer William Elderton wrote ballads as part of a career which spanned entertainment at the royal courts as well as being a lawyer at the Inns of Court.[2]

Ballads were an inherently social genre. They often opened with inclusive phrases such as ‘Come all ye…’ and included refrains which encouraged audience participation. They were sung in communal spaces such as taverns and marketplaces, at weddings and fairs – anywhere where large crowds could gather and enjoy them. You didn’t need to be a trained singer to join in, because the melodies were relatively simple and easily remembered.

Broadside ballads rarely included printed music, because few people would have been able to read it anyway. Instead, they named the tune to which they were to be sung, and these tunes relied on oral transmission. As they were passed on from person to person and learned by ear, their melodies and words underwent subtle (and sometimes not so subtle) variations. Yet without a community of singers to keep them alive, they died. For many sixteenth-century ballads in particular, all we have now is the skeleton of what they once were – the ink on the page that tells us what was sung, but very little about how.

And as a precarious academic, the irony of working on evidence which is predicated on a peripatetic lifestyle and a social context for its production and performance is not lost on me. My lifestyle, and that of many of the early career researchers I know, is characterised by short-term contracts at institutions across the country and beyond. I know people who have worked part-time at three different institutions in a week, spending one night in one city before moving on to another and another – and none of the three were where they actually lived. I know some who have worked for a term here and a term there, and others who have lurched from one temporary cover job to another, uprooting themselves and moving to a different location every year. I know more who have left academe altogether.

In my particular case, I can’t travel widely afield so instead, like many of my balladeers, I manage multiple professional personalities. The 2013 AHRC report Support for Arts and Humanities Workers Post-Phd notes that ‘In the Arts and Humanities portfolio working was found to be mainly a response to economic circumstances rather than a choice’. [3] 40% of PhD graduates ‘combined two or more jobs as a necessary strategy to secure the equivalent of full-time employment’.[4] I am a university lecturer and unpaid researcher and writer, sure, but I also do consultancy, lecturing and even study day chairing for an A level company; I write scripts for an A level revision podcast firm; I’ve written for an A level magazine; I’ve proofread and typeset a parish magazine; I give talks to community groups such as local history societies and the Women’s Institute; I work as a private tutor for GCSE and A level history and English; I’ve taught English for academic purposes; and I’m currently the administrator for the Social History Society. I’ve done GCSE invigilation on the minimum wage. I often feel like that balladeer – hawking my research and teaching to anyone who will pay me for it.

I passed my viva in 2015. For more than a year I had no work. That is the only reason I’ve got a book. I had nothing else to occupy the sixteen horrendous months when I had no income. I managed to spend that time researching my extra chapter and revising my PhD to make it into a publishable whole. Clearly, I had to have other people around me who could support me through this time – but don’t make the mistake of thinking that I’m particularly well off: supporting a family of five on one teacher’s pension isn’t all that easy, and although it was by no means the only cause of the breakdown I suffered one year in, it certainly didn’t help.

Nor did the fact that I had very few people to talk to about it. As I had no job, I wasn’t part of an academic community. I didn’t have a group of like-minded individuals around me to keep me going. I’ve always thought that I work well alone and from home, and to some extent, that’s true, but with hindsight, I work better when I know that even though I’m at home on my own, there is a community of people around me that I can turn to in order to put the world to rights. I’m supported by a convivial community in which to bounce ideas around and just talk about the things that float our boats. In short, I need an identity that isn’t based within the four walls of my home.

This is echoed by the songs I work with on a daily basis. As Mark Hailwood noted, in ballads

occupational identity is an organizing feature, and characters are routinely identified by occupational labels. Tinkers, tailors, and shoemakers, for instance, appear as social types, with associated stock characteristics. The notion that occupation defines an individual is treated as a given in ballad discourse.[5]

My ballads are populated by weavers, ploughmen, husbandmen, coopers and brewers. They are people who enjoy their work or, sometimes, are the subject of criticism when they abuse their positions in a society that valued honour and honesty. Often, their role is central to the song. I don’t think much has changed.[6] We want a sense of who and what we are. As Rosamund Paice noted in her paper for this conference, our identities are tied up with our profession. We now have, as Angela Lait puts it, the ‘problem of achieving a secure identity from among the instabilities of modern life’.[7] But what is my occupation? Hourly-paid lecturer? Freelance academic? Academic prostitute?

I certainly used to describe myself as academically homeless. Without an institution to back up our research, we lose access not just to the databases of primary and secondary source material that many of us cannot work without, but also to the support networks that share our joys when things go right and keep us going when times are tough. Conference season brings a whole new set of challenges. How do you answer the question, ‘Where are you from?’ when you are on multiple short-term contracts across several different institutions? And I’ve complained before that it’s like asking how you are – no-one really wants to know the real answer. Because the truth is: ‘Nowhere really’.[8]

*****

Ballads, however, seem to have been at the heart of early modern communities. Ballad sellers, surrounded by crowds, are seen in genre paintings right across Europe. No marketplace is complete without one.[9] Descriptions of ballad singing emphasise the communal aspects – songs sung by ‘sociable drinkers in alehouses’,[10] for example, or people who gathered with their friends in a private dwelling to hear the latest songs from a travelling balladeer.[11]

But it is interesting that although ballads are usually convivial, there are some that make explicit reference to the experience of being alone. The term is used to provide a clear contrast with the more communal aspects of early modern life, and my feeling is that there are three significant areas where ‘being alone’ figures in ballads. The first is where the singer takes the opportunity of being alone to express their inmost feelings:

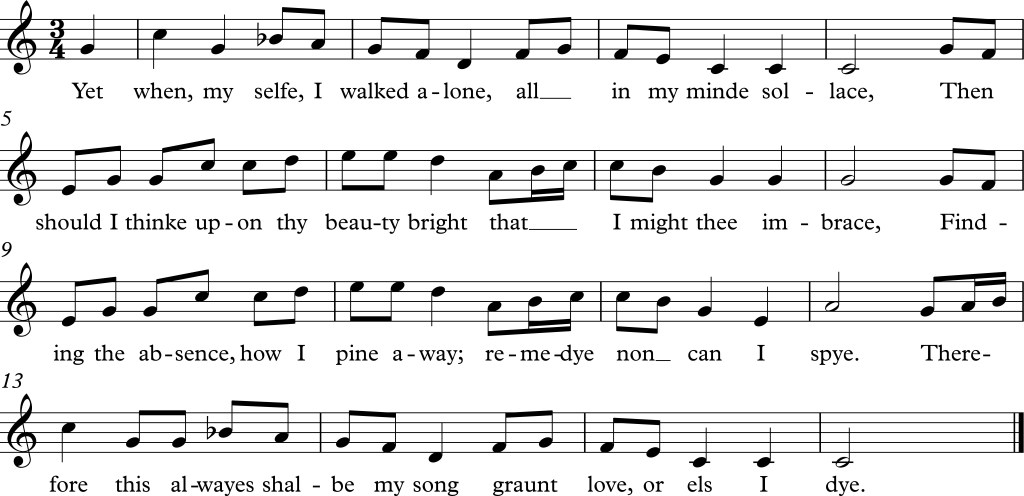

Yet when, my selfe, I walked alone,

all in my minde sollace,

Then should I thinke upon thy beauty bright

that I might thee imbrace.

Finding the absence, how I pine away;

remedye non I can spye.

Therefore this alwayes shalbe my song

graunt love, or els I dye.[12]

The second is the opportunity for the singer to overhear what would otherwise be a private conversation or soliloquy. These often address interpersonal relationships. Sometimes the singer comes across someone musing on their single state. In The Northerne Turtle, a widower is heard bewailing the death of his wife:

AS I was walking all alone,

I heard a man lamenting,

Under a hollow bush he lay,

but sore he did repent him

Alas quoth he, my Love is gone:

which causeth me to wander,

Yet merry wil I neuer bee,

till I lye lulling beyond her.[13]

On other occasions, the singer might eavesdrop on a couple discussing their affairs. For example, Martin Parker’s The Wooing Lasse, and the Way-ward Lad sees a girl coax a coy young man to return her affections, while in A Warning for Maids, the overheard conversation proves a salutary lesson for women who engage in pre-marital sex when the man whose fair words persuaded the maiden to yield in the end leaves her pregnant and alone:[14]

Now shall I be mocked of other young Maids,

they’l dout me, and say, sée how her colour fades:

She is sick for love, and forsooth they’l cry:

Her Love now hath left her, and her doth deny.

Solitude in this scenario gives the singer, and/or their subject, the chance to evaluate their position as part of a community.

The third theme is more obviously reflective, examining penitence, morality and the role of fate. In fact, these songs bear striking similarities to the later religious poetry examined by Helen Wilcox in this volume. The singer’s solitude allows them to contemplate their sinful unworthiness to receive God’s grace. Robert Burton’s abstract from the Anatomy of Melancholy is very similar in tone to the meditative ballads found in manuscript collections that I have argued elsewhere ‘allowed people to contemplate their sinful conduct and explore their relationship with God as part of their personal devotional life’:[15]

When I lie waking all alone,

Recounting what I have ill done,

My thoughts on me then tyrannise,

Fear and sorrow me surprise,

Whether I tarry still or go,

Methinks the time moves very slow.

All my griefs to this are jolly,

Naught so mad as melancholy.[16]

Being alone in sixteenth-century ballads gives people the space to tackle the great existential questions:

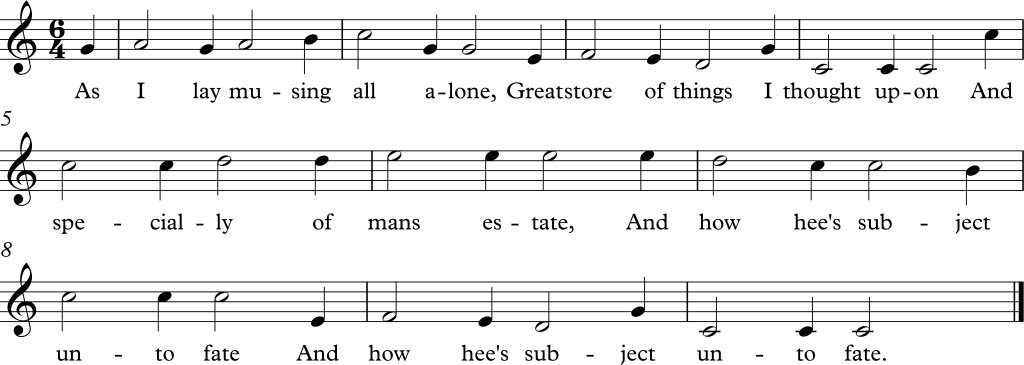

As I lay musing all alone,

Great store of things I thought upon,

And specially of mans estate,

And how hée’s subject unto fate.[17]

or to examine the subject’s relationship with God:

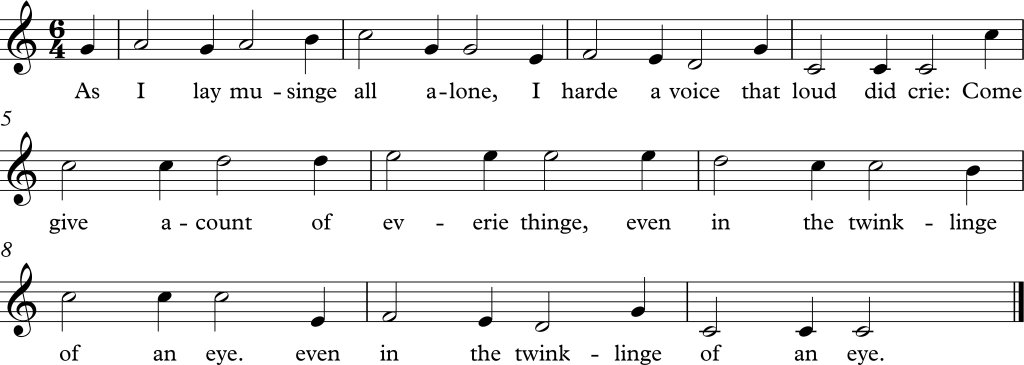

As I lay musinge all Alone,

I harde A voice that loud did crie:

Come give acount of everie thinge,

even in the twinklinge of an eye.[18]

And this sort of self-reflection is something I’ve done a lot of over the last eighteen months. I was probably invited to contribute to this discussion because I wrote a series of tweets during the University and College Union strike of spring 2020 which were tagged with their ‘precarity story’ hashtag.[19] Within days, it had been seen more than 120,000 times. One year on, it had been seen 156,800 times and had 5,160 interactions. Almost 450 people had retweeted it. It clearly struck a chord.

These were later developed into a longer, more explanatory post on my blog which discussed the context of each tweet.[20] It described my mixed feelings at going out on strike. After all, when I passed my PGCE teaching certificate I was described by the course leader as a born teacher, and I hated leaving my students to stand on a picket line to hand out union leaflets and make 21st century rough music. But our students, our children, deserve better than the exhausted, burnt out, hourly-paid staff who populate the classrooms of our universities, usually without the students even realising it.

Don’t get me wrong. I know that the permanent staff are burnt out and overworked too. But they, at least, have the luxury of being paid during the vacations. Often we don’t. This year will be the first where I am confident that I will have some work after the vacation, but the only thing I know in May is that I will have 5 dissertations to supervise – a total of 44 hours spread across the academic year. Normally, I don’t know until a few weeks before the start of term – sometimes only a couple of weeks – what, if anything, I’m going to be doing. The excuse is that universities don’t know how many students they are going to have until the very last minute.

This is down to the impact of the government’s ‘austerity’ package since the summer of 2010. It almost entirely removed public funding for Higher Education teaching and created a market where students paid fees backed by income-contingent loans. This ‘marketisation’ has been consolidated by the removing the cap on student numbers, ‘encouraging universities to maximise their income by admitting greatly increased undergraduate numbers’.[21] University leaders are now running businesses, and much of the income is spent on capital projects to attract and accommodate students. The proportion of money spent on staff has dropped.[22] This should hardly surprise us when institutions are paying large numbers of supposedly ‘casual’ staff peanuts to do more teaching than the full-time staff yet refuse to acknowledge the need to support them during the vacations. Look at the number of 10- or 11-month contracts that are offered. On one day, while working on this essay, I checked the main job vacancy site for university employment and found two of these ‘not quite a year’ posts advertised in the humanities. One might be moved to praise universities for putting what is, essentially, the same role that I have on a more formal, part-time equivalent basis. The contract might finish in June, but for the preceding ten months one would have earned around £17,000 for a part-time position – a figure I can only dream of even with my freelance work. Nevertheless, with a contract ending in June, the summer is still a huge problem.

Quite apart from the obvious problems that this type of contract creates for, say, paying rent, utility bills and or even eating during the summer, the issues are more insidious. As Hannah Leach pointed out in a recent Twitter thread, it makes it virtually impossible to move to a new city. Instead, it brings all the stress and exhaustion of long commutes and reduces us to reliance on the goodwill of friends and family. It also prevents us gaining experience from supervising MA students or continuing pastoral and academic support to students over the summer months. As Leach commented, ‘It’s hard to imagine what the point of an 11-month contract could be aside from to deprive the holder of the employment rights they would get from 12 months, or an eventual two full years’.[23] Except, of course, that it simply saves them money. On the other hand, it’s always worth noting that employees might be regarded as having been continuously employed even where there is a gap between successive contracts, such as in the summer months.[24]

But let’s get one thing straight. There’s nothing casual about ‘casual’ contracts. I go through the summer in a state of anxiety, frantically trying to get some more of my own research completed so that I have more to publish, because we have to keep publishing. There isn’t enough time at any other point in the year to do any research because we’re on a hamster wheel of read, prepare, teach, repeat. The precarious academic rarely gets to teach anything twice, we teach different courses every year, so that preparation load never seems to fall. And this burden of part-time employment and short-term contracts falls more on arts and humanities PhD graduates than it does on other disciplines.[25]

But still we keep picking up the crumbs, grateful for whatever we can get. Sandro Busso and Paola Rivetti talk about the ways in which precarious academics are particularly loyal to their universities. They describe this as ‘relational passion’ – the commitment not just to the job but to the particular workplace and the people within it. We are held there by what are known as ‘strong ties’ which are ‘particularly relevant as related to early stage researchers obtaining their first appointment’.[26] They quote research by Granovetter which shows that the level of insecurity for newly minted PhDs is high because they ‘have few useful contacts in their discipline as yet and typically rely on mentors and dissertation advisers who know them and their work well’. [27] This is what keeps us tied to a university or a department where we have strong relationships with people who might, just might, be able to help us further our careers even though our working conditions are poor.

But Busso and Rivetti go on to describe how this passion for our work and our workplaces can become a trap, precisely ‘because of the uncertainties and stress associated with [our] precarious employment conditions’.[28] They also quote research by Richard Sennett which shows that

the neoliberal evolution of the economic system leaves almost no space for positive passions such as those related to craftsmanship, which ‘sits uneasily in the institutions of flexible capitalism’. For passion to be rewarding and positive, workers need time and guarantees about their future – an unusual condition in academia.[29]

Our passion is also what might ‘replace rebellion with acceptance of exploitation’.[30] We can’t just ignore the essays that haven’t been marked at the end of the paid hours. And we self-exploit too. We feel we have to do more than we are paid for because otherwise we would be unprofessional. Then there’s the recurrent issue of the research that no-one pays us to do, but we know we have to do on top of what can be the equivalent workload of a full-time job. After all, it’s publish or perish. That’s why we deploy the rhetoric of ‘passion’ – I love my research; I care for my students – in order to justify our poor working conditions to ourselves and to others:

…passion empowers researchers to come up with acceptable accounts of their working conditions. It helps them reduce the cognitive dissonance about what their job actually is and what it should look like ideally.[31]

This is central to the lives of ECRs because we ‘need moral strength in resisting precariousness, heavy workloads, low and uncertain wages. When material rewards are lacking, passion may be the only moral justification for [our] sacrifice’.[32] But while it plays on the fact that we need the money, passion doesn’t pay the bills. It’s one of the ‘persistent myths’ of the academy – that our love of our work is more important to than material gain.[33]

If I walk out the door, there would be twenty more people just like me who would fight over the crumbs I leave behind. In fact, twenty is probably a very conservative estimate. Don’t believe me? Look what happened in Italy in 2009, when a group of adjuncts launched a campaign called ‘Teaching with Dignity’ to challenge the widespread practice of offering unpaid teaching contracts to post-doctoral fellows. Although many of the adjuncts rejected the unpaid contracts that they were offered, plenty of others stepped up to fill the gaps.[34]

Still we justify the poor treatment we receive. I was surprised that more than 50% of the ECRs surveyed by the AHRC in 2013 gave positive reasons for accepting fixed-term contracts, when the overwhelming feeling that you get reading the report is one of shrinking of academic horizons – that ECRs take short, fixed-term or hourly-paid contracts because that is all that there is; what else can you do when permanent positions are like gold dust? They might dress it up in the positive language of gaining ‘good experience’, the benefits of working for the ‘respected institution’ and accessing ‘career development’, but many of these comments came from people on longer-term fixed contracts which ran over years rather than months, or who graduated relatively recently. One does wonder how they might feel 8 years down the line when nothing has changed…[35]

*****

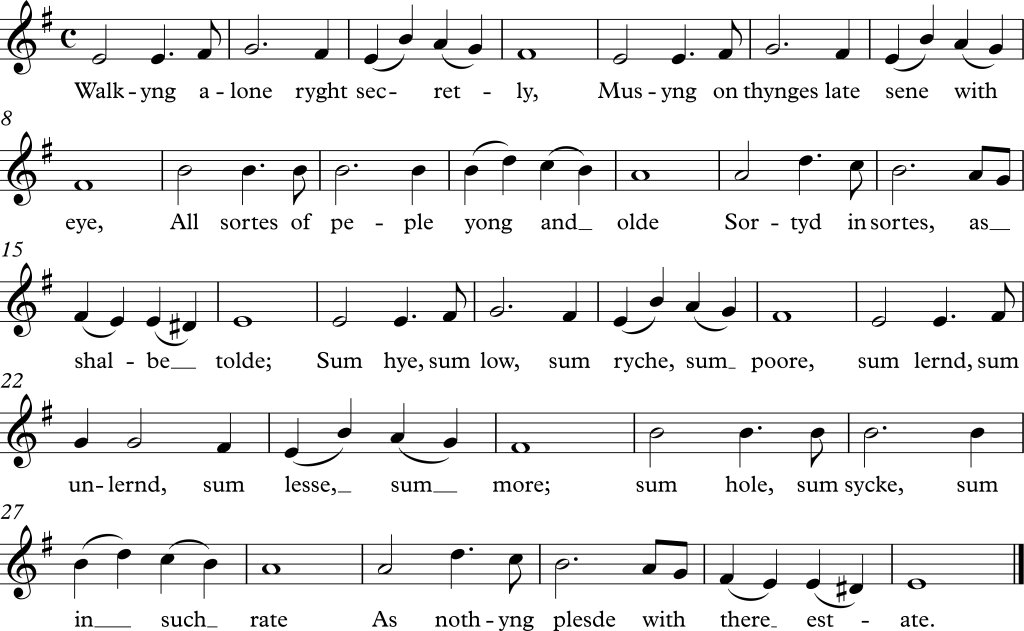

Walkyng alone ryght secretly,

Musyng on thynges late sene with eye,

All sortes of peple yong and olde

Sortyd in sortes, as shalbe tolde;

Sum hye, sum low, sum ryche, sum poore,

Sum lernd, sam unlernd, sum lesse, sum more;

Sum hole, sum sycke, sum in such rate

As nothyng plesde with there estate.[36]

Brodie Waddell noted back in 2015 that not all casual or precarious academic jobs are the same. He pointed out the difference between ‘a well-paid full-time three-year lectureship and a poorly-paid part-time nine-month teaching fellowship’ and recommended that we begin to track data on casualisation through the number of fixed-term positions advertised.[37] It is notable that there still does not seem to be any co-ordinated attempt to collect this data. The English Association have no statistics on the situation, although they have jointly (with the Institute of English Studies and University English) created a code of conduct on Employing Temporary Teaching Staff in English and Creative Writing.[38] Likewise, the Royal Historical Society has produced a similar document, Employing Temporary Teaching Staff in History Code of Good Practice.[39] But it is very hard to assess the extent of casualisation. My own contracts wouldn’t even show up on tracking the sort of data that Waddell suggested, because mine are all treated like Graduate Teaching Assistant positions. Even though I am co-supervising a PhD, I haven’t had a job that was advertised through the normal channels yet – every one I’ve got, I’ve got through word of mouth. I’m now up to 37 separate contracts [Note from 2024 = the two indefinite contracts I signed in 2022 were numbers 69 and 70!]. Someone, somewhere, devotes a spectacularly large part of their time to creating all my contracts and processing my timesheets. Wouldn’t it be easier all round if I were just made part-time?

In fact, there is no evidence that holding a succession of short-term contracts eventually leads to a permanent job. Data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency shows that in 2017/18, 67% of researchers in the sector were on fixed-term contracts, while 49% of teaching only staff were employed in this way. Of the teaching only staff, 42% were employed, like me, on hourly-paid contracts.[40] Of course, there’s an irony in the description of us as ‘teaching only’ – what it really means is that our research is unpaid, completed gratis but to the benefit of the employer, because even if the university cannot (as yet) enter it for the REF, it benefits the students and the academic community. We simply don’t have the agency to challenge this unfair system as individuals.

*****

My meanes is spent and all is gone,

and friendship now is growne cold,

Alas, I’m comfortlesse alone,

now I thinke o’th proverb old,

Which saies as long as men have means

they shall regarded be:

But having none they lose their friends,

and then comes misery.[41]

Broadside ballads are full of warnings about how you will be left alone, abandoned by your friends, if you fail to follow the social norms. But precarious academics are often abandoned by their institutions whether they follow those rules or not. Following the example of that champion of human rights, Martin Luther King Jr, the University and College Union sought to highlight the dehumanising effects of treating workers in Higher Education as tools, that is, as human resources to be deployed for the benefit of a business model, rather than human beings with rights, responsibilities and feelings.

Their report describes the casualisation of academic labour as ‘a fundamental attack on the human dignity of those caught up in it’.[42] They identified four main ways in which the casualised workforce is dehumanised. It not only limits an individual’s agency and academic freedom – it also prevents the creation of a meaningful long-term career narrative when you are buffeted from pillar to post and when you can’t even be certain that you will have a job next month, let alone next year. As many of us know to our cost, it leaves us vulnerable to exploitation – long hours of unpaid preparation, marking and student support that amount to about 45% of our labour going unpaid, and an inability to say no to anything even when we are already working every available hour just in case there’s no more work to come. But perhaps the most significant is that it ‘renders staff invisible to colleagues and institutions, treating them as second-class academic citizens’.[43] How right they are. Like my wandering balladeer who visits the communities on his trade route but doesn’t stay, I rock up at work, I teach my classes, and then I go away again. Recent research has shown that the effects of precaritisation ‘overlap to a great extent with what has been ascribed to the psychological and intellectual effects of exile’.[44] Vatansever describes this as ‘a nomadic mode of existence, with no future prospects for a steady position and, thus, with no possibility for a settled life on the horizon. It means coming to terms with being kept “in reserve” for an indefinite period of time.’[45]

Precarious ECRs are Schrödinger’s academics – simultaneously both academics and not academics. We have the PhD, but we haven’t managed to achieve a permanent position. As time passes, we can’t get funding for grants because the system still assumes that you’ll have landed a permanent job 3, or maybe 5 years after completing your doctorate when the reality is that many of us are still on casual contracts well beyond that.[46] We’re part of a department (or maybe several), but not really a full part of it, because we’re only there for a while – sometimes only there for a few hours every week and maybe without even an office in which to base ourselves. I have a friend who calls this the ‘bag lady years’ – arriving to teach with all the course materials in a huge bag, because you have nowhere else to put them and you have to carry them around with you. Before long, like my wandering balladeers, we’ll be packing up and moving on again, leaving students and staff behind.

To all intents and purposes we look like any full-time, permanent member of staff, yet we are simultaneously forgotten about for the same reason. No-one sees the invisible difference in my bank balance or, on a day-to-day basis, the reasons for my anxiety. I appear to be just like everyone else. Most of the time it’s easy for my colleagues to treat me just as they would anyone else in the department because I behave just like them and I have a full-time workload. But several of the papers presented at this conference reminded us just how easy it is to feel lonely even when we are surrounded by other people, while Rosamund Paice’s work on Thomas Fairfax (and indeed, her own experience as an academic whose job was made redundant by her institution) shows that we can suffer from professional isolation when our work identity is no longer the same as that of our friends and former colleagues. In November 2019, a permanent job came up in my department. I applied, I was interviewed, but I didn’t get it. The person who got the job is lovely and incredibly supportive, but that doesn’t make it any easier to cope with. I was and still am devastated.

Meanwhile, the things that mark me out as different are also invisible to the students. They don’t know that really, I’m only employed for a few hours each week. Some were justifiably annoyed at the loss of teaching when the UCU went out on strike because they have no idea how the universities are being run, although the #precaritystory tweets generated some very positive feedback from parents who became sympathetic when they realised just how many casual staff there are and how they are being treated. But most students (and their parents) don’t have the faintest idea that they are paying £9250 a year in tuition fees to be taught by someone who is paid for 126 hours to create and convene an entire module from scratch, or for just three hours per contact hour to do all the preparation, teaching and marking of seminars on a co-taught course.

My teaching is indistinguishable from that of my permanent colleagues. My student feedback is excellent – one described my teaching as ‘superlative, engaging and inspiring’, another praised the ‘outstanding level of teaching’, while a third advised the department at one institution where I taught that they should put me on a permanent contract before they lost me. But sometimes, we go down in students’ estimation when they discover that we aren’t what they see as ‘proper’ members of the department. I’ve had several stop calling me ‘doctor’ once they discovered I was only paid by the hour – after all, how could I be a proper academic if I didn’t have a proper job?

*****

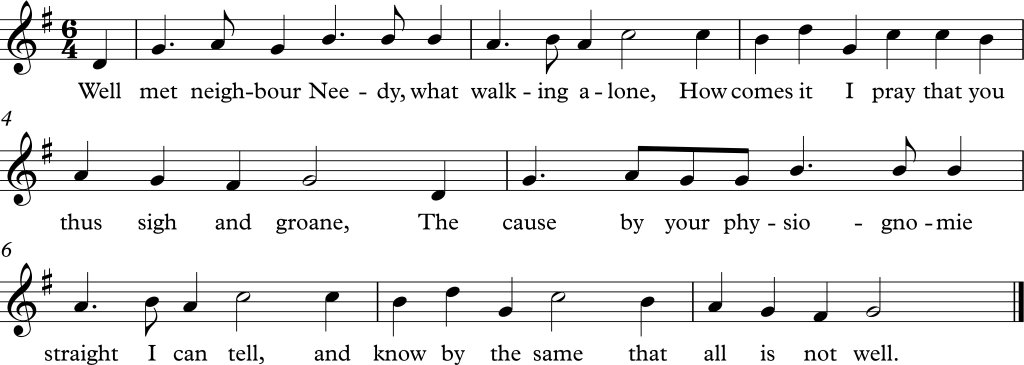

Well met neighbour Needy, what walking alone,

How comes it I pray that you thus sigh and groane,

The cause by your physiognomie straight I can tell,

And know by the same that all is not well.[47]

Are there any rays of sunshine in an otherwise gloomy picture? Well yes, there are. Just a few. The fact that I’ve been invited to speak about this at a conference that is otherwise about the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries is one of them. We are beginning to break the cycle of isolation and invisibility. The problem of academic precarity and its effects on the mental health of the workforce is beginning to be recognised, but there is much more work to be done.

My invisibility was breached by my #precaritystory tweets. Some of my colleagues discovered just what I’d been asked to do over the preceding 18 months and the fact that, at that time, I was my 25th short term casual contract at a single institution. These weren’t 25 ongoing or back-to-back contracts – some lasted far longer than others. They ranged from 30 minutes to 132 hours; from running welcome week introductions through delivering 6 seminars a week across 2 different first year courses, to setting up an entire course from scratch from someone else’s single paragraph outline and supervising sixteen dissertations and a PhD. Some of the contracts were on timesheets; some were paid monthly. Work comes and goes and is often at the very last minute. I still never get paid the same from one month to the next, except, of course, in summer when I don’t get paid at all. It’s almost impossible to keep on top of, and it makes life incredibly hard work. It took a whole morning in April to check that I’d been paid correctly so that I could complete my tax return – and no-one pays me for that time!

But on the UCU picket line, a few of the staff from my department cooked up a plan, or more accurately, a petition. Following the strike, they wrote a letter which highlighted the problems I was facing and, quoting the university’s new policy on the use of fixed-term contracts, asked that the Head of Department request that the Dean put me on a permanent contract. Almost every member of the department co-signed that letter. I’m not sure I’ve ever been more touched by anything in my life. What they didn’t know was that the Head of Department had already undertaken to attempt this on my behalf.

*****

A few weeks before the Loneliness conference, I was privileged to take part in the writing of a communal ballad about the exploitation of goodwill in the neoliberal university, facilitated by the Post Workers Theatre as the culmination of their residency at the University of Gothenburg. During our discussion of precarity I commented on how worried I was that my keynote was going to be full of doom and gloom. Professor Rajani Naidoo reassured me with the words, “You don’t need to be positive: you need to be true. People need to see just how bad things are”.

So yes, it would have been lovely to end this essay with the news that collegial action by permanent staff on behalf of their exploited co-worker had led to secure employment. But two weeks after my colleagues sent their petition, a global pandemic caused chaos and then, a recruitment freeze, and what was probably my last hope went up in smoke for the foreseeable future. As one of the letter’s authors put it, “I just can’t believe how shit our timing was in the end”.

I don’t have a positive way to round off. For all that my job is to think, I can’t think of a solution. As Vatansever notes, ‘… the frightening pace of labour devaluation does not seem to be paralleled by a corresponding rise of resistance to it from the ranks of academia’.[48] All I can say is that something has to change. The impetus for that change needs to come from a culture of inclusion where those in secure positions stand beside us to fight on the behalf of the precarious workforce. In the words of my anonymous balladeer, ‘Therefore this alwayes shalbe my song / graunt love, or els I dye’.

[1] A knotte of Good Fellows, in The Shirburn Ballads 1585-1616, ed. Andrew Clark (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1907), p. 91. The song is to be sung to the tune of ‘Stand thy Ground, Old Harry’, which is lost, but the eminent ballad scholar Claude Simpson suggested that the tune might be the same as ‘Have at thy Coat, Good Woman’, to which the song is here set. Claude Simpson, The British Broadside Ballad and its Music (Rutgers: New Brunswick, 1966), p. 291. The title of the paper is taken from A merye new balade, how a wife entreated her husband to have her own will (London, 1568). The author would like to thank all the people who helped to make this paper possible, including Brodie Waddell, Rebecca Fisher, Eleri Cousins, Deborah Sutton, James Bowen, Rajani Naidoo, Dash MacDonald, Demitrios Kargotis, Joanna Figiel, Stevphen Shukaitis and Nicholas Mortimer.

[2] Jenni Hyde, Singing the News: Ballads in Mid-Tudor England (Abingdon: Routledge, 2018), pp. 34-5. For more on the careers of Sheale and Elderton, see Andrew Taylor, The Songs and Travels of a Tudor Minstrel: Richard Sheale of Tamworth (York: York Medieval Press, 2012) and Hyder E. Rollins, ‘William Elderton: Elizabethan Actor and Ballad-Writer’, Studies in Philology, 17:2 (1920).

[3] Kay Renfrew and Howard Green, Support for Arts and Humanities Researchers Post-PhD Final Report (The British Academy and AHRC, 2014), p. 21.

[4] Robin Mellors-Bourne, Janet Metcalfe and Emma Pollard, What do researchers do? Early career progression of doctoral graduates (Vitae/The Careers Research and Advisory Centre, 2013), p. 11.

[5] Mark Hailwood, ‘Broadside Ballads and Occupational Identity in Early Modern England’, Huntington Library Quarterly, Volume 79:2, (2016), pp.187-200, p. 188.

[6] Andreas Hirschi, ‘Callings and work engagement: Moderated mediation model of work meaningfulness, occupational identity, and occupational self-efficacy’, Journal of Counseling Psychology, Vol 59:3 (2012), pp. 479-48.

[7] Angela Lait, Telling tales: Work, narrative and identity in a market age (Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2017), p. 49.

[8] Jenni Hyde, ‘It’s Like Asking How You Are’, https://jennihydeacademicservices.wordpress.com/2019/07/03/its-like-asking-how-you-are/ [accessed 22 July 2022].

[9] Jenni Hyde, ‘From Page to People: Ballad Singers as Intermediaries in the Graphosphere’, in Scripta in Itinere. Revista internacional de historia social de la cultura escrita 2018, ed. by Antonio Castillo Gómez and Verónica Sierra Blas (Gijón: Trea, forthcoming).

[10] Mark Hailwood, Alehouses and Good Fellowship in Early Modern England (Woodbridge, Boydell Press, 2014), p. 127.

[11] Jenni Hyde, Singing the News: Ballads in Mid-Tudor England (Abingdon: Routledge, 2018), pp. 119-122.

[12] A Most Pleasant and new ballad of a young gentleman and young gentlewoman, in Shirburn Ballads, p. 223. the tune of ‘Pity Me’, to which this ballad should have been sung, is lost. The conjectural setting here, to the later tune of ‘The Moon Shall Be in Darkness’, was for the purposes of performance only and should not be taken to indicate that this was the intended tune for the song. William Chappell, Popular Music of the Olden Time, 2 vols. (London: Cramer, Beale and Chappell, 1859), II, p. 739.

[13] The Northerne Turtle: Wayling his vnhappy fate, In being depriued of his sweet Mate… (London: 1628), STC (2nd ed.) / 18671.3.

[14] Martin Parker, The Wooing Lasse, and the Way-ward Lad… (London: 1635),STC (2nd ed.) / 19284: Richard Crimsal, A Warning for Maides… (London: 1636), STC (2nd ed.) / 5430.

[15] Hyde, Singing the News, p. 201.

[16] Robert Burton, The anatomy of melancholy… (London, 1621), STC (2nd ed.) / 4159, unnumbered page.

[17] Richard Crimsal, A comparison of the life of Man… (London: 1634), STC (2nd ed.) / 5416. The set tune, ‘Andrew Barton’ is lost. The words are conjecturally set to the contemporary tune ‘John Dory’ from 1609, simply because they fit and the melody suits the reflective nature of the words, but again, this should not be taken to imply that I think the words were intended for this tune– indeed, the last line of the words needs to be repeated to accommodate the final phrase of the music. Simpson, British Broadside Ballad, p. 399.

[18] London, British Library, Add MS 38,599 (Shann Family Commonplace Book), f. 145r, set to ‘John Dory’, with the same caveats as above.

[19] Jenni Hyde, https://twitter.com/wallyberry/status/1230407973580812289?s=20 [accessed 12 April 2021].

[20] Jenni Hyde, ‘Precarity Story – The Blog’, https://jennihydeacademicservices.wordpress.com/2020/02/22/precarity-story-the-blog/ [accessed 12 April 2021].

[21] Stefan Collini, ‘The Marketisation of Higher Education’, Fabian Society, 22 February 2018,https://fabians.org.uk/the-marketisation-of-higher-education/ [accessed 22/02/20].

[22] ‘Latest figures show increases in universities’ income, surpluses and reserves’, University and College Union [hereafter UCU], 26 April 2018,

https://www.ucu.org.uk/article/9450/Latest-figures-show-increases-in-universities-income-surpluses-and-reserves [accessed 12 April 2021].

[23] Hannah Leach (@hmleach), ‘When I saw this listing I was SO psyched…’, Twitter, https://twitter.com/hm_leach/status/1400788786087436291 [accessed 11 June 2021].

[24] UCU, Survival Guide for Hourly-Paid Staff: Help and Advice for Hourly-Paid Employees in Adult, Further and Higher Education (2015), p. 19.

[25] Renfrew and Green, Support for Arts and Humanities Researchers Post-PhD, p. 21.

[26] Sandro Busso and Paola Rivetti, ‘What’s Love Got to Do with it? Precarious Academic Labour Forces and the Role of Passion in Italian Universities’, Recherches sociologiques et anthropologiques, 45:2 (2014), pp. 15-37, https://doi.org/10.4000/rsa.1243 [accessed 11 June 2021], para. 23.

[27] Mark Granovetter, ‘The Strength of Weak Ties : A Network Theory Revisited’, Sociological Theory, 1:1 (1983), pp. 201-233, quoted in Busso and Rivetti, ‘What’s Love Got to Do with it?’, para. 23.

[28] Busso and Rivetti, ‘What’s Love Got to Do with it?’, para. 25.

[29] Richard Sennett, The Culture of the New Capitalism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), p. 105, quoted in Busso and Rivetti, ‘What’s Love Got to Do with it?’, para. 26.

[30] Busso and Rivetti, ‘What’s Love Got to Do with it?’, para. 31.

[31] Busso and Rivetti, ‘What’s Love Got to Do with it?’, para. 48.

[32] Busso and Rivetti, ‘What’s Love Got to Do with it?’, para. 17.

[33] Asli Vatansever, At the Margins of Academia: Exile, Precariousness and Subjectivity (Leiden: Brill, 2020), p. 9.

[34] Busso and Rivetti, ‘What’s Love Got to Do with it?’, para. 51.

[35] Renfrew and Green, Support for Arts and Humanities Researchers Post-PhD, pp. 31-33 & 41.

[36] John Redford, The Goodness of All God’s Gifts, in The Moral Play of Wit and Science and Early Poetical Miscellanies, from an Unpublished Manuscript, ed. by James Orchard Halliwell (London: Shakespeare Society, 1848), pp. 97-8. This is a conjectural setting because no tune is indicated in the manuscript. The setting is to ‘Fortune My Foe’ because it fits the metre, but this should not be taken to imply that this was the intended melody for the song. Simpson, British Broadside Ballad, p. 227.

[37] Brodie Waddell, ‘Students, PhDs, historians, jobs and casualisation: some data, 1960s-2010s’, The Many Headed Monster, https://manyheadedmonster.com/2015/09/08/students-phds-historians-jobs-and-casualisation-some-data-1960s-2010s/ [accessed 12 April 2021].

[38]Personal correspondence with Rebecca Fisher, Chief Executive Officer, The English Association, 7 June 2021; The English Association, Employing Temporary Teaching Staff in English and Creative Writing http://www.universityenglish.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Good-Practice-Guide-Employing-Temporary-Staff-in-English.pdf [accessed 11 June 2021].

[39] Royal Historical Society, Employing Temporary Teaching Staff in History Code of Good Practice, https://files.royalhistsoc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/17204714/RHS-Employing-Temporary-Teaching-Staff-in-History-Code-of-Conduct.pdf [accessed 11 June 2021].

[40] Nick Megoran and Olivia Mason, Second Class Academic Citizens: the Dehumanising Effects of Casualisation in HE, (n.p.: UCU, 2020), p. 6.

[41] Richard Crimsal, John Hadlands advice: Or a warning for all young men that have meanes… (London: 1635), STC (2nd ed.) 5422. Its tune, ‘The Bonny Broom’, is extant, and is taken from Simpson, British Broadside Ballad, p. 68.

[42] Megoran and Mason, Second Class Academic Citizens, p. 3.

[43] Megoran and Mason, Second Class Academic Citizens, p. 6; UCU, Counting the Costs of Casualisation in Higher Education: Key Findings of a Survey Conducted by the University and College Union (London: UCU, 2019), p. 4.

[44] Vatansever, At the Margins of Academia, p. 4.

[45] Vatansever, At the Margins of Academia, p. 5.

[46] See the British Academy Postdoctoral Fellowships, https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/funding/postdoctoral-fellowships/ [accessed 11 June 2021], in which the limit is 3 years from the viva; the UKRI ESRI Postdoctoral Fellowships, https://www.ukri.org/opportunity/esrc-postdoctoral-fellowships/ [accessed 11 June 2021], in which the limit is 1 year post-viva; and Leverhulme Early Career Fellowships, https://www.leverhulme.ac.uk/early-career-fellowships [accessed 11 June 2021], for which applicants must be within 4 years of submitting their PhD thesis. Even the most recent addition to the list, the Royal Historical Society Early Career Fellowship Grant Scheme, https://royalhistsoc.org/grants/rhs-early-career-fellowship-scheme/ [accessed 11 June 2021], requires applicants to be within three years of submission.

[47] E. F., A dialogue betweene Master Guesright and poore neighbour Needy… (London, 1640). Simpson links the tune of ‘I Know What I Know’ to the verse of the familiar tune ‘Lillibulero’, to the opening of which it is here set. Simpson, British Broadside Ballad, pp. 449-53.

[48] Vatansever, At the Margins of Academia, p. 9.

Leave a comment