This is third in a series of three posts about the Social History Society Conference.

On Wednesday I woke up early and couldn’t get back to sleep. This gave me plenty of chance to ponder what we’d heard so far. That morning I chaired a panel in the Environment, Heritage, Spaces, and Places strand: ‘Landscape, Environment and Social Relations in Early Modern England’. Nicola Whyte spoke first on ‘Order and Disorder in Early Modern Landscapes’. Nicola talked about things being out of place and the moral landscape. Her work on landscape history is based on alternative archival sources that demonstrate vibrant, entangled histories of relationships with landscape, especially around enclosure. The meanings of field boundaries went from being common knowledge-based to physical boundaries that indicated ownership. New forms of boundaries cut across ideological and physical landscapes.

People at the time thought that private was secret – personal identity was subsumed within the whole – people didn’t see themselves as an individual part of the whole but as a constituent part of the social whole. The meanings and functions of landscapes shifted – it was an integral part of the social whole too. Her paper tried to complicate the binary between order and disorder. Using the quarter session records, she wanted to bring landscape to the fore in the interactions in the records – to show how it fitted with neighbourliness and good order around practices of dwelling. The landscape was central in some cases, being a central player in the disputes. Ideals of neighbourliness were not just about speech and interpersonal action, but also destruction of the environment or inappropriate use of the landscape. They were informed by customary practice and were made and remade repeatedly. Meaning was drawn from the landscape itself.

Andy Wood then gave us a paper on ‘The View from Mousehold Heath: Contesting Landscapes of Lordship in the 1549 Rebellions’. He wanted us to think about the politics of Kett’s rebellion and how this connected to the landscape. Communications with rebels were initiated by the royal heralds, but there was bloody fighting between the rebels and the royal forces. The rebels established a camp on Mousehold Heath, and three lists of rebel demands survive – two are in the Cecil papers. They picked Mousehold because it was outside the east side of the city of Norwich, a city with significant social tensions. The site is a place of conflict between rural and urban as well as the rich sheep farmers and the urban industrialists. It had been the subject of a prophecy in 1537, further prophecies circulated in early 1549. There were a substantial number of rebels but their leaders gathered under the Tree of Reformation, probably the oak tree used as a preaching place, where they announced their demands. Oak trees were often the site of hundredal councils, so they were drawing on the existing authority of the site. It had a degree of local legitimacy. They were taking over the structures of local legitimacy, as the Pilgrims had done in 1536. They put themselves in opposition to what they saw as the ‘traitors’. They were using their sense of the local past to create a new vision for the future. A lot of the articles are about returning to an earlier world – the first year of the reign of Henry VII, which is just within living memory. Coincidentally, the paper was given on the anniversary of the rebellion!

The final paper was ‘The Weardale Cheat and the intangible archive, c.1610-1656’, given by Simon Sandall. The chest was the product of an effort to convert the customary landholding in the area to tenancy. The oral tradition was collated in written records which were stored in the chest. Testimony, surveys, decrees, and witness documents were gathered alongside legal opinions from lawyers. There was a long-running dispute over landholding and the contents of the chest was hugely important. But Heselridge ignored one type of written evidence – the depositions describing popular memories of the landscape – in favour of the other, legal information. Heselridge was the main opponent of Cromwell in parliament in the 1650s, and the depositions were in part an attempt to drown him in paperwork when he was anyway busy. There were pages and pages of genealogy not detailing the lands but the inheritance of tradition. Many of the deponents were from the oldest members of the community and many were from yeomen.

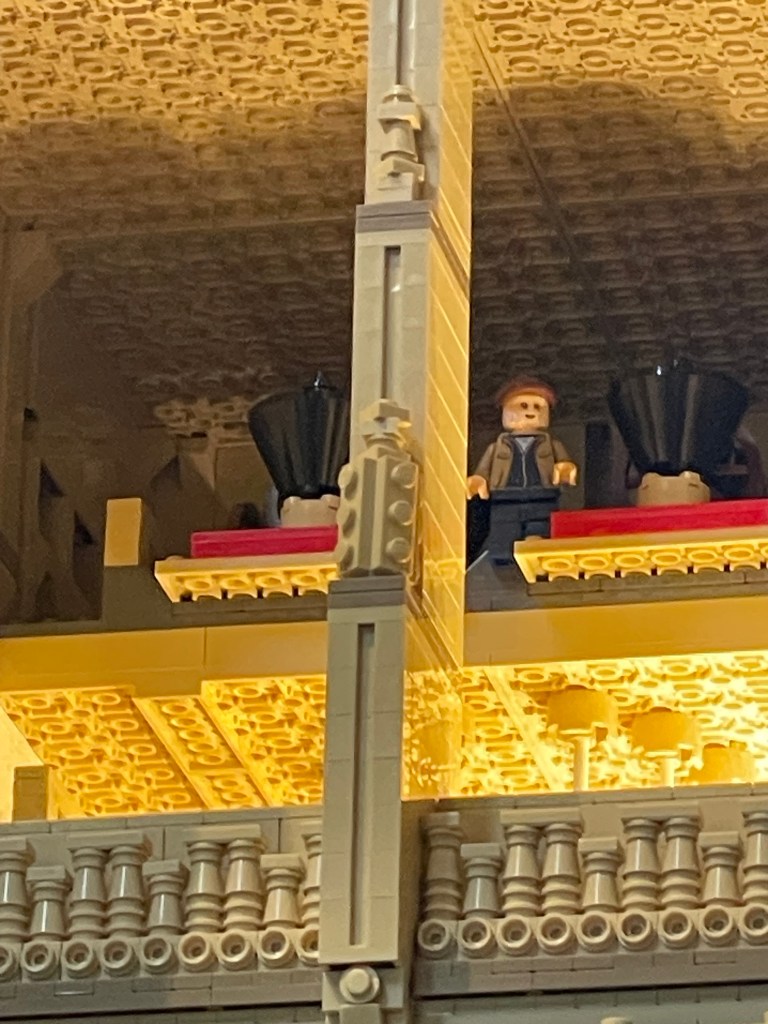

After the first panel I sneaked off with another delegate to look at the cathedral, which was beautiful. We were really stuck by the difference in sound between the chapter house, where you could hear every word being said by anyone anywhere in the room, and the body of the church, where the sound was subdued even though there were lots of visitors chatting away, so it was still very peaceful. I lit a candle at St. Cuthbert’s shrine, and we went up into the museum to see the Lego cathedral. We walked down into the centre of Durham and caught an Uber back up to the science park.

After lunch Elena Ghiggino chaired the final panel in the Work, Leisure, and Consumption strand, Work and Identity in England. First, Mabel Winter spoke about ‘The Millers’ Tales: the socio-economic world of millers in England, 1315-1815’. Millers were central to early modern communities because diet was essentially grain based. They were targets of accusations of sexual deviance and malpractice. It was a job open to anyone who could do it satisfactorily, and there was little training required – they have no guild. They leave little record because of this and the fact it was generally women and servants who interacted with them. She supplemented analysis of the literary representations with research into the litigation involving millers.

The literary representation is predominantly based on Chaucer’s Miller from the Canterbury Tales. But the reality was that they worked the largest machines of their day and there was some mystery about how they worked. Gests, tales and songs normalised the view that millers cheated their customers, taking an excessive toll of the grain they processed. Plenty of cases demonstrate that there was cheating going on, suggesting that the ballads might be right. But millers weren’t owner occupiers and had to pay rent, so the owners’ poor practises contributed to the millers’ crimes.

They are also portrayed as a bit stupid, and the records suggest that they did tend to be uneducated in the classical sense, and this made it relatively easy to swindle them. Nevertheless, the job was quite skilled and dangerous. There were two guilds, one in York and one in Newcastle, and there were differences between the skills needed for horse, wind and water mill. There were different types of mill custom – borough mills owned by corporations, manorial mills where people had to use the mill, and tenant mills. Most millers were men, and female millers were rare, but they might run the miller’s store, or be their householder where they handled the tolls.

The next paper was ‘“Bodily labor is hard for me”: Identity and the Working Body in Early Modern England’ given by Tyler Rainford. He argued that the public perception of the self was central to the person’s reputation and identity. He based his paper on the diaries of Robert Meek (1656 – 1724), an Anglican minister from Slaithwaite in West Yorkshire, who began writing a diary aged 29. He was a perpetual curate and constantly a lodger, and yet relatively well off. He clearly had a problem getting up in the morning, which rather hit a note because I was struggling to stay awake not because there was anything boring about Tyler’s paper, but because I hadn’t slept well. Still, Meek thought that physical labour of any sort was tiring, and he distinguished between physical and spiritual labour whilst still acknowledging that they were mutually advantageous for the community. He confessed to staying up late and drinking too much, and although the occasions were fairly rare, he seemed to feel guilty about them. Wasting time in drink was sin and he believed that it should be punished. He also seemed to be distressed by the occasions on which he found it difficult to study, and Tyler noted that this might be performative. What is key here is the sense of having done work was more important than precisely what one did.

The last paper was from Peter Wood. This was on a much more modern topic, ‘“Very well, but tell me – what has homelessness to do with housing?” How did we get from vagrancy in 1939 to homelessness in 1979?’ He started by pointing out that in 1939 no one was ‘homeless’ and in 1979 there was almost no one classified as a vagrant. There is no agreed definition of homelessness, so he was interested in what people in the post war period thought they were talking about when they talk about homelessness. He also suggested that the question was really about entitlement – the entitlement to a home, who has it and where. Vagrancy was abolished in WWII and then the post-war welfare state, and the solution to vagrancy was in both cases about work – people became entitled to help because they paid National Insurance through work. This was one pillar of the welfare state alongside National Assistance and the National Health Service. People’s status was not just defined by statute but also by their accessing the National Assistance programme. The entitlement was limited to temporary accommodation. He claimed that homelessness was born in 1970 when Heath’s Conservative manifesto pledged to redefine homelessness. There was a fundamental shift in the understanding of homelessness as being about housing not welfare at this time.

Leave a comment